My close friends and colleagues know I love obits.

I probably bore others talking about them. I tweet them. And I send them as emails to acquaintances I think might be interested in the subject’s life or work.

My mother may have been responsible for this mild obsession, as she never missed what she called “the death notices” in the Dayton Daily News or Journal Herald. But then again, she used to read the newspaper from the back to the front. At least I don’t do that. Perhaps that’s a subject for another blog post.

Well-written obituaries—such as those I read daily in the New York Times—are like onions. They have layers that can be peeled back to learn just a little, or a lot. Many obits have great lessons for marketers, and that’s what I’ll explore in this post.

The Inner Core

Obituaries are like mini-biographies. Most of us probably read those of the “greats”—celebrities or artists, war heroes or composers, inventors or business giants, especially if their subjects died earlier than expected. Maybe it’s just reassuring to know that Death is an impartial equalizer, the ultimate common denominator of our humanity. We’re still here, reading about the "greats." And they’re not.

Like a good biography, an obit gets to the heart of the matter by letting the reader know what made the person tick: the passion, the inner core that motivated and inspired him or her to greatness. After all, these people must have had something going for them to get coverage in the Times.

The first lesson from obits for marketers then is to try to understand how the deceased transformed his or her inner core into a life’s work. How did they market themselves, their ideas or establish their personal brand? Sometimes this guiding principle takes root at an early age, and leads the person on a direct path to fame or wealth or both.

But often—and this makes for a better, more interesting lesson for us mere mortal marketers—the subject of the obit took a more serendipitous route in following his or her inner core. For me, these are the personalities, many of whom don’t have recognizable names, who are most inspirational.

For example, how can you not love the story of André Cassagnes, whose obituary I read in February 2013? Who? Just think Etch A Sketch. In conceiving of this legendary mechanical toy, Cassagnes didn’t create the demand for artistic self expression; it had always existed. What he did remarkably well was to create a simple device that satisfied the demand, and to do it in a fun and low-cost way that appealed to just about everyone. That was his genius. And Etch A Sketch was just the first product inspired by his inner core; in later years Cassagnes went on to become France’s foremost maker of competition kites. That sounds like fun.

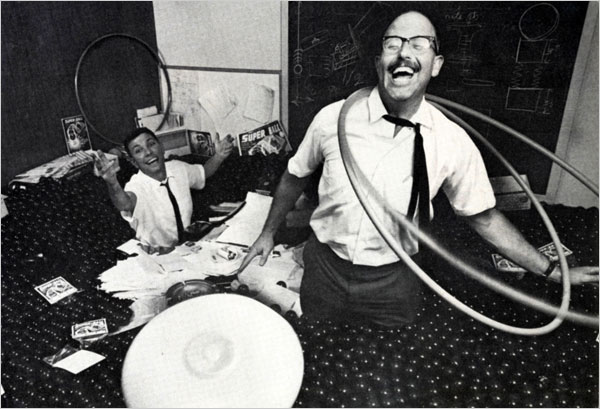

Or how about the 2008 obituary for Richard Knerr? His name isn’t familiar, but who among you didn’t have a Frisbee or a Hula Hoop, or stop dead in your tracks in front of the TV to watch a Wham-O commercial when you were a kid? Those TV spots were classic, mesmerizing. Interestingly, Knerr never claimed to have invented these iconic toys. But he was a master marketer who understood exactly what it was about a silly plastic plaything that resonated with his customers, regardless of their age.

Master Marketer Richard Knerr, right, and "Spud" Melin in 1965, at the height of the Frisbee and Hula Hoop craze. Knerr never claimed to have invented these toys. Instead, he was often heard to say he was the "originator" of the two novelties. Wham-O actively solicited or crowd-sourced new ideas from the public. Photo courtesy New York Times.

Unsafe At Any Speed

I want to go into some detail regarding a more recent obituary, one that is a great example of the value of these short prose pieces to marketers: “Richard Grossman, 92, Crusading Publisher of 1960s.”

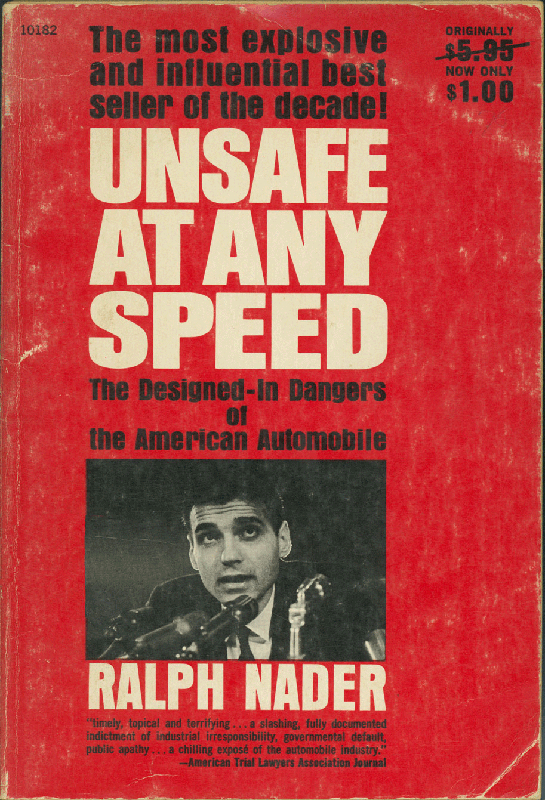

The February 1, 2014 obit in the New York Times focused on Grossman’s career as a Manhattan publisher, notably bringing out Ralph Nader’s seminal work on the design deficiencies of US-manufactured automobiles, Unsafe At Any Speed, in 1965. That book helped start the modern consumer movement. Before that—and here was the obit’s first clue that Grossman had good marketing bones—he started an advertising agency in Canton, Ohio and wrote an advertising column for Fairchild Publications.

Grossman's marketing instincts and writing and editing skills played a big part in making the book a best seller and a driver of the fledgling consumer movement of the 1960s.

From a marketing perspective, what is amazing about Unsafe At Any Speed is that Grossman edited the pages as Nader wrote them. The pair had two typewriters set up side by side in a Washington DC hotel room and knocked out the manuscript, working day and night, in just three weeks. Grossman brought to the book his own instincts, his inner core, on what would sell Nader’s ideas to the public. And, of course, his editing, along with his naming the book and marketing it, was a big part of what made it a bestseller and activist manifesto.

The “publicity masterstroke,” according to the obit’s author Douglas Martin, was Grossman’s scheduling of the book’s launch in Detroit’s Sheraton Cadillac Hotel. Car executives intentionally stayed away in droves, leaving Nader the sole center of attention as he answered questions from Motor City’s press corps.

Choosing and Changing

Plenty of marketing lessons already in this obituary! But there’s more, even better ideas to be mined. Grossman had diverse interests, and he went on to become a psychotherapist, authority on alternative medicine, and published expert on Ralph Waldo Emerson. Wow, what a career.

One of the great things about obits is they usually list the best biography or the books the deceased may have written. So, an obituary is a great place to begin finding out more about somebody with whom you weren’t previously familiar. Like me finding out about Richard Grossman.

I wanted to see what sort of writer he was, so I went on Amazon and found an inexpensive used copy of one of his books, now out of print, noted in the obituary: Choosing and Changing: A Guide to Self-Reliance, published in 1978. It is a small but handsome 140-page book printed on quality rag paper that was a delight to handle and read.

He was 56 or 57 when he wrote it and admits in the acknowledgments that it was “an attempt to flesh out, in modern terms, the major themes of Emerson’s classic essay on ‘Self-Reliance.’” Grossman is an insightful thinker and skilled writer, and I could carry on at length about what I learned in this 36-year-old book.

The Different Natures of a Company

But I’ll limit myself to telling you about just one marketing idea that I extrapolated from the book. Let’s go back to the onion analogy I used earlier. In an early chapter, Grossman writes about the human personality as made up of three layers:

Sometimes, great marketing lessons are to be found in the least likely places.

- The public nature: those aspects that become visible in the roles you play as a member of society.

- The private nature: the parts of yourself that come into play in your most intimate encounters with family and close friends.

- The personal nature: the inner core of the consciousness, which observes and directs your outward behavior, and that is the true source of your own individual destiny.

The author continues,

Such an anatomy of personality permits us to think of ourselves in new ways. Learning more about how public, private, and personal selves are interconnected can help us to see what is unique about us. It will show us how to merge our special values and goals with our obligations to other people. Above all, it will enable us to define the vocation that is the heart of true prosperity.

Marketing: The Study of Human Nature

Grossman was a student of human nature throughout his career; it was his real vocation, so to speak, even in his marketing heyday. I don’t think he would mind our transposing these ideas to the business arena. Rather than the three natures of a human being, think of a company’s personality or natures. The pieces fall in place beautifully in helping marketers to better understand their company’s inner core, the passion that originally created the product or service, and the real story that needs to be told to customers.

“From my perspective, it is the marketer’s job to make sure this inner core isn’t buried or lost in the shuffle.”

There is the public nature the company shows to its many outside stakeholders, the press, the community at large; a private nature that is understood by employees and sometimes--and this should come as no surprise--even by competitors; and a personal nature that is, well, the most telling and important. This third nature is the vision, the inner core and the combination of special values and goals that most likely served as a wellspring in the company’s founding.

Telling the Company's Unique Story

In a company too, these three natures need to be interconnected if it is to be successful. From my perspective, it is the marketer’s job to make sure this inner core isn’t buried or lost in the shuffle. His or her task is to make sure the private nature is a telling part of the organization’s public and private natures, and to communicate the company’s intrinsic values and goals. To tell the unique story that underlies its obligations to its customers and defines the company’s product or service better than any competitor can.

I could go on, but I think you get the point of this wonderful lesson in marketing communications from Richard Grossman. And of my original premise that obituaries can be gold mines for marketers.

Related Articles

The Art of Market Positioning

Most of the Affluent Aren't Brand Conscious

The Thankfully Short Life of the Ultra-Yacht